February 1946,

the beginning of the end

Malmö was not at its most inviting in February 1946. The temperature in the southern Swedish city was just above zero and the conditions an unpleasant mix of rain and snow. If you’re familiar with this particular kind of weather, you’ll know how it permeates your clothing and numbs the soul. It is the weather of despair rather than of hope.

The young woman was late, running up the long winding stairs of the Malmö Stadsteater. Finding her way had taken far longer than anticipated, and she really should not have been this late. The traffic and finding a parking space had been a nightmare. In fact, life had been a bit hectic recently, and the reviews of her performance in Eurydike in Gothenburg far from complimentary. “Staccato,” was what the critic had written! “A monotone intonation”; critics can be so cruel. Maybe she was working too much – work was everything now. Today was important; this could be a vital step in her career. Being on stage with the two rising stars of Swedish theatre, George Fant and Irma Christensson, and in a play by John van Druten, a recognised playwright. Perhaps not as famous as Clifford Odets, who had written her first big role in Rocket to the Moon, but that now seemed a lifetime ago, although it had only been three years. But it didn’t matter; she wanted progress, she wanted to move on. “Thank you, Papa Jooss, for teaching me how to take feedback.”

The young man standing at the top of the stairs would be directing ‘The Voice of the Turtle’ (Turturduvan). It was one of the first plays he’d be overseeing on his own. He was tall, dark-haired with a friendly yet inquisitive gaze. The first thing he noticed were her eyes; they were truly special, large and full of expression. Her red hair had evidently lost the battle for attention, though it was usually what stood out about her. She was also what Americans would call petite – short, slim and fit, a trained dancer really, though her acting talent had shone through when she danced in Karl Gerhard’s variety show a few years back.

Surely, he must have had her comic talent in mind for this comedy; she would be the perfect fit for the part. But did he notice her slim body? Her well-trained appearance was the result of years of hard physical training and the pitch-perfect body control she had achieved. All that dancing and practice, not to mention her use of choreography and one’s body to tell a story. We do not, and cannot, know; Gösta Folke is dead and so is Agneta. They both passed away in 2008, Agneta after suffering from severe dementia.

At this point, neither of them could know they would spend most, if not every day, of the rest of their lives together. Over the coming decades they would both be well-known members of the Swedish theatrical community. They would be in the movies, on stage and in the media much more than either of them had been up to that point.

Being a public person means you leave traces, which become your legacy, whether you like it or not. Without any reference to accuracy. These traces will represent who you were perceived to be. A trail of newspaper clippings, photos, interviews, reviews, radio and TV performances. So we know the ‘official’ narrative, which is that the story of Agneta and Gösta began that day. More or less out of nowhere and by chance, as so often in life. However, when you look at what is written about Agneta, there is something not quite right; a strange gap in Agneta’s history from the late spring of 1943 to late 1945. It is as if a piece of the puzzle is missing. The steady trickle of newspaper clippings stops and there is silence for nearly two years.

30 years of analytical work has taught me many things. That human beings are really bad at being rational, and that they are, to a very great degree, controlled by their emotions. That complexity makes predictions of the future wholly inaccurate. That the human psyche’s greatest strength is its ability to adapt. Yet, at the same time, that no activity is more trying or painful for human beings than change. It requires an enormous effort. Moreover, I have learned that the first mover in any matter has a huge advantage over opponents, because those opponents will have to confront the first mover’s arguments or performance before they can begin to address their own ideas. Finally, that we are, as a species, suckers for confirmation. Our confirmation bias is striking, and if you are in any doubt about this, consider the power of marketing. We love to see what we are looking for but fail only too often to see reality for what it is.

This brings us to a lesson that is even more important in the context of this history – the questions we do not ask. We are frequently unable to see what we are not expecting, and this blinds us to strikingly obvious observations.

Take this example. In 1993, one of my best friends from university was getting married. Not only was he a very good friend, but he was also an exceptionally bright intellectual, a straight ‘A’ student if ever there was one. Not long before their marriage, my friend and his wife-to-be had bought a small farm in the south of Sweden and started renovating it. Naturally, as wedding presents, they wanted things that could help them complete their project.

Me and some of his other university friends were invited to the wedding, and we wanted to support them in their effort. Our first thought was to give them some paint for the large barn on the estate. But we then decided to not just give them the paint, but to also paint the barn. However, to ensure it was a surprise, we had to do this at night before the wedding, which was taking place on Midsummer’s Eve. Thanks to Sweden’s short summer nights, we managed to paint the barn before dawn and go to bed in our sleeping bags inside the barn. The barn was now the traditional warm red colour you see throughout Scandinavia. By chance, I woke up early and happened to see my friend stepping out onto his porch. He had to walk some 50 meters from the house to the barn to let some chickens out. He noticed nothing! It wasn’t until he was literary half a metre from one of the walls that he noticed some dripped paint on the ground, and then he realised everything had changed. No one had told him that the barn would change colour during the night.

The question we do not ask, the things we do not expect blind us to seeing what is clearly visible in front of us. The question that we do not ask is the most important.

So, according to the available sources, it appears as though Agneta Prytz’s life story really took off in February 1946, that it all began in Malmö. She had just resumed her stage career a few months earlier, while Gösta had started getting his first major opportunities as a theatre director. So here is where the story of Agneta Prytz and Gösta Folke began.

In my what you might describe as ‘illustrious’ family, Agneta and Gösta belong to the category that those of us far less interesting would be watching from afar. You knew about them, while they to all intents and purposes may have had no idea you even existed. Especially after the dissolution of the family trust in 1970, which removed the occasional large family gatherings that had happened for many years in the past. There was a book, though, printed in 1964, which listed all the members of the Mellgren family in great detail. It clearly states that Agneta was married to Gösta Folke, the director, and that was that – no other husband. Yet we now know that there was a lot more than was publicly known. This is the unknown or forgotten history I intend to reconstruct from the ground up, with as many details as can be added.

Where should we begin our reconstruction? Dear reader, as you may have already guessed, you can begin telling a story at any point, or rather, history has many beginnings. Although there is no official starting point, there may be points that provide some logic to the events that follow. 1916 is such a year; it is a point where logic provides some structure.

1916

1916 was an annus horribilis if ever there was one. The Great War had been going on for more than 17 months, and on the Western Front a stalemate had developed that had turned ideas of courageous charges into slaughter. Machine guns mowed down men, and the war had already added both the rolling barrage and poison gas as notable features. The old world order was in the process of committing suicide.

At the start of the year, Björn Prytz’s younger brother Frank was already injured out of the 2/20th Battalion of the County of London Regiment (Blackheath and Woolwich) that he volunteered for on 6 August 1914, amongst a wave of young men eager to join the fight. He had attended St. Dunstan College and also been a member of its Officer Training Corps, so he clearly had military ambitions. However, he was only 17 and his application had to be signed by his mother, Theresa. Today, the thought of signing one’s child’s voluntary admission to the armed forces appears strange, to put it mildly, but during the Great War it was not uncommon for underage young men to volunteer. Certainly, in 1914, many saw the war as an exciting adventure.

Basic training was undertaken in the South of England, and finally Frank and his comrades were shipped to France on 9 March 1915. Frank survived the Battle of Festubert in May 1915 but was injured in the shoulder on the first day of the Battle of Loos on 25 September 1915, when the Battalion, as part of the 47th Division, attacked the southern flank of the front. Frank was one of 171 casualties in the battalion, the lowest loss rate of any of the attacking battalions of the 47th division. You could argue he was lucky, as other parts of the division fared far worse. Overall, the Battle of Loos was an almost complete failure, with the British suffering 59,247 casualties for no gain of territory. Insufficient artillery fire, insufficient reserves, and failed logistics prevented the exploitation of early gains. For the first time, the British were using chemical weapons (chlorine gas), which proved almost as lethal to the British troops as to the Germans.

There are many songs that capture historic events, but few, in my view, better capture the madness of war, the pain of loss and the grieving for a loved one than this:

A Swede in German service

At the same time, a young Swedish engineer was working long shifts at the Hansa Brandenburgische Flugzeugbau in Brandenburg am Havel, just north of Berlin. His name was Karl Lignell, the eldest son of Carl Lignell, banker, entrepreneur, supporter of the arts and would-be architect. Karl had dreamt of becoming a pilot ever since Baron Carl Cederschiöld flew his Blériot over his hometown of Östersund in 1911. However, Carl Lignell, who himself had instead dreamt of becoming an architect, wanted his son to become just that. Luckily for Karl, he succeeded in convincing his father to let him study engineering in Germany instead, and in 1912 he moved to Mittweida in Eastern Germany to enrol at Technicum Mittweida, then Europe’s largest private technical institute, to study mechanical engineering. Following his final exams in 1914, he returned briefly to Sweden to do his military service at the nascent Royal Flying Corps (Kungliga Flygkåren) at Malmslätt before returning to Germany, where the outbreak of war had set the development of aviation into high gear. In May 1916, Carl succeeded in getting a job with Camillo Castiglioni’s1 fast growing aviation empire – Die Hansa Brandenburgische Fluzeugbau AG in Brandenburg am Havel, just north of Berlin.

New models continually entered service, and either side could only retain the upper hand until its opponent was able to field its next model. Aviation was the industry to be in for a young engineer. This new weapon was undergoing rapid development. At the outbreak of the war, it was unclear what the aeroplane could be used for. By 1916, however, it had found several distinct roles; the fighter plane, the bomber, the reconnaissance plane and the floatplane that could land on water. Hansa Brandenburg was by this point known for its large floatplanes used for long-range reconnaissance. Karl’s manager, chief designer Dr. Ernst Heinkel2, had already begun building a reputation that would make him one of Germany’s most important aircraft designers.

The work was taxing, and Karl could not expect much in the way of rest or holidays. In fact, the work was more like being in the army. War had changed society fundamentally. I have copies of his passports from both 1912 and 1916. The pre-war version reminds you of a modern European passport, because there are no stamps. Borders in pre-war Europe were open and controls limited. The latter one, in contrast, is littered with stamps marked ‘Militär Politzei’ (Military Police). Europe closed in 1914 and would only really reopen when the Schengen Agreement was introduced in 1995. There is a certificate that has been kept, dated 8 March 1918, granting Carl four weeks leave for medical reasons, signed by his manager, Ernst Heinkel. Whether he was allowed to go back to Sweden to visit his family for a few weeks was up to the military authorities to decide. After all, he knew all the latest designs and was a walking security risk. Appreciated for his hard work and keen interest in everything related to aviation, he had started a long and very successful career, which will intersect with our story on several occasions.

Meanwhile in France

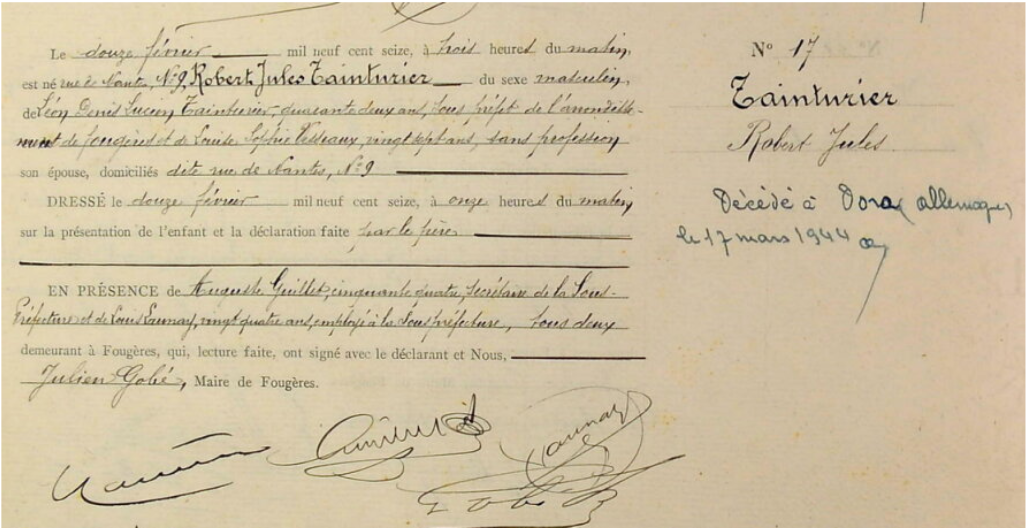

For Lucien and Louise Tainturier, the year had begun positively, as Louise was pregnant with their second child. On 12 February, at 3 a.m., their second son was born at No.9 Rue de Nantes in Fougères, Ille et Vilaine. Mother and child were both well. At the age of 42, Lucien already had a long career as a public official and he was now the Sous-Prefét3 in the Département Ille et Vilaine. He had already become a father in 1901, when Marie Gougelat gave birth to their son, Pierre. However, they were not married, which seems very unusual for the time. A woman giving birth outside of wedlock was socially stigmatised, in this case particularly so since the Gougelat family was relatively well-off and Lucien was a public official, being Chef du Cabinet du Préfet de la Côte-d’Or at the time. Unfortunately, I have not found any explanation as to why this happened, but it appears out of the ordinary. A few years later, in 1904, Lucien and Marie married and Pierre is mentioned in their marriage act as legitimised, i.e. with Lucien accepting fatherhood of the boy. Unfortunately, his first marriage was short-lived; Marie Tainturier died in 1912 aged only 32.

Lucien did not remain a widower for long. On 14 April 1914, Lucien married his second wife, Louise Tainturier (née Vasseux), and on 11 November 1914, she gave birth to their first child, Henri Tainturier. With the subsequent arrival of Robert, the family now had three sons, two of whom had been born to the rumblings of war.

Louise was happy that Lucien was a little older and therefore not called up. However, the extra work put on public officials due to the war resulted in him being away most of the time. But he was alive, and she did not have to bear the anguish that all mothers and wives with sons and husbands at the front had to endure.

On 21 February 1916, at 7.15 in the morning, ‘Unternehmen Gericht’, the Battle of Verdun, began with a massive German barrage. The Germans had been delayed, however, as their initial plan had called for the offensive to begin on 12 February at 5.00 in the morning. For 10 hours, 808 artillery pieces fired 1,000,000 shells to make up for the delay. Over the following nine months, three weeks and six days, more than 300,000 men would die and 450,000 would be injured in one of the bloodiest battles in human history. These figures do not reflect the psychological injuries, but modern war’s effects on the human psyche gradually became undeniable as thousands of men went insane from their experiences in the trenches. It proves you can, in a way, be dead while still being physically alive.

This short film may provide some insight into what it means to be shell shocked:

This was a battle that would define history, both in the short term and for decades to come, as its consequences were so far-reaching. The German strategic rationale for the attack was to bleed the French army to death by attacking where it was forced to use its reserves. This idea has come to signify the slaughter of the Great War and the industrialisation of killing in modern warfare. The Battle of Verdun is also a symbol of France’s successful defence against the attacking Germans, and it made Maréchal Phillippe Pétain into ‘le lion de Verdun’. The battlefield itself remains a scar on the face of the Earth to this day.

A better deal

While Frank Prytz narrowly escaped death at Loos, his elder brother Björn escaped the war entirely. Both brothers had a Swedish father, Gustav Prytz, and an English mother, Theresa née White Ward (White-Ward?). Initially, the family had lived in Gothenburg but, due to the depression in the 1890s and Gustav’s financial problems, they had moved to London in 1893. In 1905, Gustav and all his children were granted British citizenship. In all, there were eight Prytz children, and Björn was the second-eldest, born in 1888.

Björn spent most of his childhood in England and attended Dulwich College from 1900 to 1903. While the classical programme focused on Greek and Latin, Björn chose to follow the new modern programme, which offered studies in mathematics, French and German. After completing his time at Dulwich College in 1903, Björn spent time in Gothenburg before pursuing his luck in Berlin, working in insurance while also moonlighting as a language teacher for the Berlitz Language School. In 1905, he got a job with AB Separator’s German subsidiary, which involved him selling in the German and Belgian markets.

He then spent a brief period in Algeria selling Swedish industrial products, before rejoining AB Separator, this time in its marketing department in Stockholm. He stayed with AB Separator until 1913. His close friend Raoul Nordling, who at the time was the deputy Swedish Consul in Paris, claims it was he who suggested Björn work for SKF, the ball-bearing manufacturer, which brought him to Gothenburg. However, before that, he met Ingrid Prytz, the daughter of wealthy Tobacco manufacturer Erik Mellgren4 and his wife Elisabeth.

In 1912, the Erik Mellgren Tobaksfabrik was still the largest producer of tobacco, cigarettes, cigars and snuff in Sweden, despite rumours of possible nationalisation. The government needed money to pay for pensions and defence, and the tobacco industry was seen as a stable source of revenue for the government. Health concerns were not part of the equation, and such considerations would only come much later on.

In Gothenburg, everyone knew Erik Mellgrens Tobaksfabrik, located at Vallgatan 40. Erik had inherited the company together with his brother Anders, and they jointly managed the business. Their nine sisters were not included in the ownership, despite the fact that it was the matriarch, Hulda, who had managed the company for many years following the early death of her husband.

Erik and Elisabeth had five children, and Ingrid, also known as Pim, was the eldest, born in 1888. Fortune had smiled on the Mellgren family, who enjoyed a high quality of life. In 1912, the family alternated between their apartment at Haga Kyrkogata 14 in central Gothenburg and a summer residence of their choice.

Artistic talent and musicality were common amongst Hulda’s 12 children and remain common amongst their descendants. Erik was a good singer, though nowhere near as good as his sister Anna who had real star talent, and had been a member of the Orphei Drängar male choir during his law studies at Uppsala University. The Mellgren family was also involved in philanthropy, providing support for the local symphony orchestra and the Gothenburg Opera. Erik was deputy chairman of Göteborgs Orkesterförening, the local symphonic orchestra, from 1908 to 1934, and Erik himself occasionally also sang on stage.

Since Elisabeth’s sister Gerda had married the painter Richard Bergh5 in 1890, painting was also enjoyed by family members, and some had the opportunity to tap into Richard’s expertise. This also explains the many portraits of Mellgren family members by Richard Bergh, including the one below of Ingrid painted about 1912.

In her memoirs Hervor Mellgren, Ingrid’s younger sister, describes a loving atmosphere where the children enjoyed a good deal of freedom. Elisabeth and Erik’s home was open to friends and family. Guests were frequent and entertainment included music and cultural events as was common amongst society’s upper classes at the time. Gerda and Richard where not the only representatives of culture. Hanna and Georg Pauli were close friends of Elisabeth and Erik. Georg Pauli was a painter and teacher at the Valand Art School in Gothenburg and his wife was also a painter. Because of this friendship their son Torsten was included in the home-schooling that Elisabeth provided to Ingrid and Hervor. They were taught by Elisabeth until 1899 when Ingrid and Hervor both started at the Nya Elementarskolan.

Dear reader, I do not know why the Mellgren children were taught at home. In this period wealthy people often had a private teacher. But the liberally minded Elisabeth may also have objected to the often strict and religious practices of schools at the time. One observation form Hervor’s memoires is that the Mellgren children were free spirited and allowed to roam around. This photo from 1912 shows the girls dressed as you would expect at the time. Pretty dresses, laces and hats. That did not prevent them from secretly catching rides with the horse drawn brewery carriages or climbing lamp posts. The latter a skill that young Ingrid was particularly good at.

Eventually, in 1899 the girls were allowed to join a public school, which suited Hervor better than Ingrid. While Hervor thrived at Nya Elementarläroverket för flickor, even though it was an old-fashioned and strict institution Ingrid did not. She was not adapting to the strict curriculum. Their parents nurtured very different ideals. Therefore, in 1901 the families Mellgren, Frisell, Ekman, Hedlund, Mannheimer, and Berg decided to start a more modern school based on progressive ideas of pedagogy and open to both boys and girls. This was the first school in Gothenburg that mixed boys and girls. An important inspiration was the internationally renown Ellen Key, political thinker, author and promoter of women’s rights. In the new school there would be no grades, practical and theoretical subjects should have the same importance in the curriculum and there would be no physical punishments. It would also be non-confessional, and religion would be taught so that believers of all confessions could take part. In short its vision was a school for happy children. Elisabeth was deeply engaged in this project and as many in this day convinced about the positive social potential that education would unlock. But before this initiative was even started Ingrid’s unsatisfactory situation at school was had to be resolved. On the initiative of Elisabeths sister Gerda, Ingrid was sent to attend homeschooling in the Fåhreus family at Ekenäs gård just outside the small town of Flen. She was to be the companion of their daughter Vera.

The school opened in 1902. Younger brother Gunnar began from the outset, and Hervor also started there in 1905. Pim however, due to her being considered weak would never study there. In 1908 Hervor were amongst the first in the new school to pass the baccalaureate.

Pim on the other hand would continue her home schooling until she started attending the Whitlockska Skolan in Stockholm. I have no information explaining this decision, however it is interesting to note its profile. Just like Göteborgs Samskola this is a radical institution. It mixes boys and girls it is non-confessional and it is also based on the ideas of Ellen Key. Therefore, it appears a bit strange to send one’s child to Stockholm to attend just the type of school the family had founded.

Dear reader, at this juncture facts are failing us. So far I have failed to uncover precisely how Ingrid and Björn met. But it appears likely that the lively and social Ingrid meets Björn in Stockholm in 1911. Until further notice this will have to be our assumption. It cannot have been a very difficult decision making process since their wedding was planned for the spring 1912.

The wedding took place in Gothenburg In line with the custom of the day the wedding was announced on March 19. The wedding took place on April 4 at the Gothenburg Town Hall. Ingrid’s deeply religious grandmother Hulda was greatly upset by such pagan practice but attended none the less. The wedding party was a large gathering of family and friends held at the Mellgren’s apartment in Haga Kyrkogata 40. Björn’s parents were there having travelled from London. As always in the Mellgren family singing was an important part of festivities and Erik had written a new text to Wagner’s Lohengrin’s wedding song, which was performed to great acclaim.

The newly wed were given a sendoff by boat to go to Marstrand. Any one with a bit of insight to Swedish spring weather knows it is notoriously unreliable. This particular night was cold with a light snowfall. As the skipper of the boat lost directions it meant that the newly wed did not arrive at Marstrand until 2am in the morning, tired, cold and slightly seasick.

Politically, it was a liberally minded family, and Erik Mellgren was elected as a member of Gothenburg City Council (Stadsfullmäktige) for the Liberal Party from 1905 to 1930. In addition, he was a member of the Financial Committee (Drätselkammaren) that managed the city’s finances from 1909 to 1913 and again from 1918 to 1928. He was also on the School Board (Folkskolestyrelsen) 1896 to 1911 (as chairman from 1905 to 1911). This meant participation in many important processes and influence over the management of Sweden’s second-largest city and a key industrial hub. During Norway’s struggle for independence in 1905 the Mellgren’s sided squarely with the Norwegians wishing them independence from Swedish reign. Erik Mellgren also stood once as a liberal candidate for the Riksdag, Sweden’s parliament, losing by one vote for not voting on himself.

The combination of financial wealth, a good position in society and an open mind to the world and the evolution of human thought meant that Erik and Eliabeth viewed their children’s ambitions in a comparatively modern way. Besides the family’s broad cultural interests, growing up in the Mellgren family at the start of the 20th century taught you opportunity and ambition over tradition and custom. If you were a Mellgren in Gothenburg in the first decades of the 20th century you were well known and well connected. So Björn and Pim marrying was a step up on the social ladder for a young, aspiring man of modest means. However, Björn’s decision to accept an offer from AB Svenska Kullagerfabriken (SKF) would soon propel his professional career to new heights. In February 1913 they welcomed their first child, Kenneth, and in 1914 their first daughter, Teresa.

SKF was the brainchild of Swedish inventor Sven Wingquist6, who in 1907 invented the multi-row self-aligning radial ball-bearing, an invention that allowed anything movable to move more easily and better than ever before. Critically, the new ball-bearing was able to adjust for imperfections in axle machining, vibrations and movement, which made it more reliable than previous products. Machinery, trains, ships, cars and aircraft were all completely dependent on ball-bearings. Consequently, the SKF franchise grew quickly into a multinational company. In 1912, SKF was represented in 32 countries, and had production facilities in 12 countries and 21,000 employees.

Björn was employed in one of Sweden’s many international manufacturing successes, as innovative and transformative in its day as tech companies today. His international marketing experience and broad language skills were valuable for a company like SKF. So, despite only being 26 years old, he was quickly promoted to head of marketing. Competition in the ball-bearing industry was fierce, both domestically and internationally. The answer was expansion and in-market consolidation; you either ate or were eaten. In October 1914 it was decided to send, Björn to the US to investigate opportunities to expand the SKF franchise; war and the growth of the automobile industry were promising trends for the business. In 1915, SKF acquired the American manufacturer The Hess-Bright Manufacturing Co. in Philadelphia, opening the American auto industry to SKF products. Since The Hess-Bright Manufacturing Co. had been producing the ‘Conrad’-ball bearing under licence from its owner the Deutsche Waffen Fabrik, the idea was floated to launch SKF products under a unique brand name. Björn then came up with the idea to call the new brand Volvo, Latin for ‘I am rolling’. A Swedish limited liability company was registered on 5 May 1915, but products were eventually still labelled SKF in the US as well.

The acquisition was managed by Björn. In spite of the ongoing world war and the intensifying U-boat attacks, Björn was sent to America to conclude the deal and manage the US operations. The Ellis Island registry shows that Björn left Christiania7 aboard the Skandinavien-Amerika Linjens (SAL) liner SS Hellig Olav on 4 June and arrived in New York on 18 June 1915. Surprisingly, Ingrid was there to welcome him, having sailed ahead of him on 26 April on the same ship, arriving in New York on 6 May 19158. Their two small children, Kenneth was two years old and Teresa only one were left with their grandmother Elisabeth and a nanny. Although leaving them behind in Sweden is almost an impossible thought for a mother these days it was none the less the decision by their parents. Hervor notes this in her memoires without any emotional consideration, just stating the fact. The decision was simply to not expose the small children for this long trip to and from the US. Björn’s task was the acquisition and not permanently staying.

The day before SS Hellig Olav’s arrival in New York harbour, the German submarine U-20 under the command of Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger sank the RMS Lusitania off the Irish coast with the loss of 1,197 lives. The sinking of the Lusitania marked a turning point in the Great War, with public opinion in the US beginning to swing in favour of joining The Entente in the war against Germany and her allies. The strong reactions to the sinking of the Lusitania forced the German High Command to halt the unlimited U-boat war. The ruthlessness that characterised the German attack and the German decision to start using poison gas were acts that further dehumanised the war. The irony was that ships of other nations were temporarily spared, but that would change when the German High Command again altered course.

In early 1916, Björn had to return once again to the US. A letter dated 18 March 1916 from Elisabeth to her daughter Hervor Wickman in Paris indicated that Björn was travelling to the US. We can also conclude that Pim was pregnant again when Björn left Gothenburg. As time will tell, it was a parting gift.

Apparently Björn’s return to the US required him to go via England. But his British passport became a liability; on arrival in England, he was banned from leaving for six days. If he got through, he would send a telegram with the message ‘All right’, if he was drafted into the army, he would instead send a telegram with the message ‘Congratulations’. This journey was a bit of a mystery though, since there are no records of him entering the US in 1916. The Skandinavien-Amerika Linjen’s route was from Copenhagen to Christiania and then to New York; there was no stopover in England. Björn may have decided to travel from Norway to England to visit his family and then to continue on to the US. While this is possible, it was also much riskier, since British ships were still being targeted by German submarines and because of the risk posed by Björn’s citizenship.

From letters kept, it is possible to glean the thoughts of, in particular, Elisabeth Mellgren. She was appalled by the senseless brutality of the war, and many in her active social life expressed similar opinions. There was a resentment among the Gothenburg social elite towards the warring parties in all countries. It is also clear that, despite the conflict, no one party was regarded as being more responsible for the conflict, so a negotiated peace at this stage and in these circles was not regarded as one party’s unconditional surrender. However, although discussed, peace negotiations led to nothing.

The peace initiative arranged by Henry Ford in 1915, known as the Peace Ship, had failed. The initiative was mocked by the press both in the US and in Britain. The subsequent peace conferences in Stockholm and The Hague, where Europe’s women had jointly called for an end to hostilities, had also come to nothing. The forces in favour of peace could not defeat those that believed in the importance and benefit of pushing on until the opponent’s defeat.

As spring turned to summer in 1916, Pim was pregnant once again, and their second daughter was born on 4 December. She was named Ingrid Agneta Prytz. Ingrid and her children spent Christmas together with Elisabeth and Erik. They had just moved from their apartment on Haga Kyrkogata 14 to the family’s brand-new townhouse, Villa Mellgren, at Bengt Lidnersgatan 5. This was situated in Lorensbergs villastad, a development for the well-heeled. More or less all villas bear the names of their owners. There is Villa Ekman, named after the famous trading house dynasty, Carlanderska Villan, after the chairman and co-founder of SKF, and Broströmska Villan, after the famous shipping magnate, to name but a few9. Living here was a strong sign of a family’s social status. New luxury homes continued to be built in Sweden in spite of the ongoing war. And, amid low interest rates, the inflationary bubble was expanding rapidly thanks to unlimited exports of war-related material to Germany, in particular, but also to Russia. Credit was cheap and asset prices were soaring.

These economic conditions created a group of people known as the Goulash Barons (Gulaschbaroner), who continued living very comfortable lives while a growing portion of the working classes had significant difficulty making ends meet. The uneven distribution of gains and losses, whereby those who were indebted had their debt reduced by the rise in inflation, while those on low incomes or with a little money in the bank were hit hard, was a recipe for disaster. Social dissent was on the rise and the demand for workers to unite would soon be heard around the world. But in 1916, dissent was less visible. In this context, Erik and Elisabeth were old money, but still able to finance the construction of a roomy villa.

A war-weary world was increasingly questioning the madness of the industrial-scale slaughter. However, the fighting was yet to reach its ultimate crescendo. In January 1917, the German High Command resumed its unlimited U-boat war. Björn was still in the US and Pim was about to return to him with the children; this time, they were going to stay indefinitely.

In Brussels, at that time a three-year-old boy had been orphaned and placed with foster parents. He was far removed from the opportunities that would open up to the newborn Agneta and Robert. His name was Georges Delfanne.

Footnotes

- Camillo Castiglioni is no longer the famous name he was in the early part of the 20th century. In many ways, he is not unlike some of today’s tech billionaires. Born in Trieste in 1879 and the son of the chief rabbi, his legacy remains to this day, not the least in Bayerische Motoren Werke AG (BMW), as well as in Bayerische Flugzeugwerke or Bf, an abbreviation that is forever associated with Willi Messerschmitt’s many aircraft. Find out more here: Camillo Castiglioni – Wikipedia. There is also interesting material on YouTube, in particular, if you understand Italian. ↩︎

- Dr. Ernst Heinkel was a pioneer in aviation before 1914 and became the chief designer at Hansa Brandenburguische Flugzeugbau during the Great War. His career was only in its infancy, and he remained a key figure in German aviation into the Second World War. For more about him, please see Ernst Heinkel – Wikipedia. ↩︎

- In French administration, the Préfet is the central government representative in a department, with significant powers ensuring the precise execution of policy or “Cette magistrature était l’une des institutions les plus monarchiques que l’on ait jamais pu imaginer” as count Vaublanc expressed it in his memoires Mémoires de M. le comte de Vaublanc, Vincent-Marie Viénot de Vaublanc, éditions Barrière, p.407, 1,857. ↩︎

- Following the nationalisation of tobacco manufacturing in 1914, Erik Mellgren was a member of the Board of Directors for AB Svenska Tobaksmonopolet from 1914 to 1918. He was a labour dispute conciliator in the western district 1920–26, a member of the board of the Gothenburg School of Business 1921–35, a superintendent 1924–32 and a supervisor at the Filip Holmqvist Business Institute. ↩︎

- Richard Bergh was a prominent painter in Sweden around 1900. Born in 1858, he trained first in Stockholm and later in Paris. His debut was at the Paris Salon in 1883. He belonged to the group known as ‘Opponenterna’ (The Opponents) together with painters Carl Larsson, Per Hasselborg, Ernst Josephson and August Hagborg. You can read more about him here in Swedish (Richard Bergh – Wikipedia), in English (Richard Bergh – Wikipedia) and in French (Richard Bergh — Wikipédia (wikipedia.org)). ↩︎

- Sven Gustaf Wingqvist was a Swedish engineer and inventor who first worked in the textile industry for AB Gamlestadens Fabriker, where he realised how to improve the low-quality ball-bearings available at the time. His ideas came to revolutionise how machines move. For more about this extraordinary man, please follow this link: Sven Gustaf Wingqvist – Wikipedia. ↩︎

- Christiania was the name of the capital of Norway until 1 January 1925, when a decision was made to revert to its ancient name, Oslo. The meaning of the name is debated, but it may mean the plain by the ridge or the plain of the gods. ↩︎

- In Ingrid’s customs documents, her address is City Club Hotel on 55 West 44th Street in New York. There is no information indicating that she was accompanied by any children. Interestingly, she is stated as being of British nationality, while Björn is stated to be Swedish when he arrived in the US a few weeks later. The opposite was true. ↩︎

- For more details on this interesting part of Gothenburg, which is a good illustration of the close-knit elite that is one characteristic of the industrial centre, please follow this link (requires knowledge of Swedish): Lorensbergs villastad – Wikipedia. ↩︎